Design 4 Project

Maninder Singh & Fatima Shahzad

Project Overview:

Long Island is experiencing a growing workforce shortage directly tied to the region’s lack of affordable housing. Young, highly educated professionals entering the job market often begin with modest salaries and significant student debt. For many, the cost of living on Long Island is prohibitive, forcing them either to relocate elsewhere or for local businesses to consider alternative solutions. One such solution is the development of corporate-sponsored incubator housing—affordable living arrangements that help workers establish themselves during the early stages of their careers. Research indicates that once workers put down roots on Long Island, they are far more likely to remain, contributing to the long-term vitality, growth, and leadership of the region. Thus, incubator housing is not only a matter of affordability but a strategy for economic sustainability and regional

resilience.

Project Site:

The site is the 58,000 SF (former) Swissair Headquarters located at 41 Pinelawn Road at the corner of North Service Road, Melville, NY.

Background Research

(Workers Housing)

Founder of Port Sunlight:

William Hesketh Lever (Lord Leverhulme): Industrialist + philanthropist who believed industry should improve workers’ lives. He invested profits in housing and amenities rather than direct cash handouts — quote paraphrase: “I shall use it to provide… nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.”

Model: “Co-partnership” / welfare capitalist approach — combine good living conditions, education and recreation to create a healthier, more loyal and productive workforce. Typical late victorian industrial housing (densely packed terraces)

Architects of Port Sunlight:

Port Sunlight was developed by William Hesketh Lever, who hired around 30 different architects starting in 1888. The names of these architects are William Owen, Grayson and Ould, and John Douglas. They had the job to design the village for his soap factory workers. The first houses, built in the early 1890s, were largely designed by the Warrington-based architect William Owen, often in partnership with his son Segar Owen. Over time, other architects from Liverpool, London, and other regions were brought in to contribute to the project.

Housing Design:

The houses differ in style, materials, roof shapes, and detailing. This gives the village a picturesque and non-uniform appearance. Common styles include Tudor Revival, Elizabethan, Queen Anne, and Arts and Crafts.

Material Used For Homes:

Local brick, half-timbering, roughcast plaster, and red or slate roofs were used. Decorative chimneys, bay windows, and gables added individuality to each home.

Port Sunlight Layout:

Garden village design which was inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement and early garden city principles. Houses were arranged along curving streets, village greens, and open spaces rather than rigid grids. There was an emphasis on natural scenery, with parks, gardens, and tree-lined avenues. Public buildings (church, school, community hall) were placed centrally to encourage a sense of community. The factory was located to the north, separated by green belts to keep the residential area peaceful and clean.

Peter Rowe's Theory Analysis

(Design Thinking As A Process)

Essen-Katernberg

What it was: Coal-company worker colonies near the Zollverein mine in the Essen district of Katernberg—brick row-house settlements like Hegemannshof and Ottekampshof laid out with repetitive but humane dwellings, gardens, and service buildings. Built largely 1890–1895 onward; expanded into the interwar years as Zollverein grew.

Client/driver: Primarily the Zollverein mining company (Haniel family) rather than Krupp; however, it’s part of the same Ruhr “welfare capitalism” landscape as Krupp’s housing.

Urban + architectural character: Long rows of modest brick houses (1-2 stories) with tiny front gardens, rear plots, stables/sheds—planned for self-provisioning. Street grids were simple and walkable to pits, washhouses, and shops.

Community facilities & green: Estate plans incorporated kitchen gardens, tree-lined streets, schools/chapels, and co-op shops (typical of Ruhr colonies). Later expansions added more housing between the wars. Today the area sits next to the UNESCO World Heritage Zollverein complex.

Margarethenhöhe

What it was: A purpose-built garden-city suburb endowed by Margarethe Krupp (1906) via the Margarethe-Krupp-Stiftung, then designed and built in stages by Georg Metzendorf (main build 1909–1934/38).

Scale today: The foundation still manages ~3,100 residential units and ~60 commercial units—Germany’s largest housing foundation.

Urban + architectural character: Picturesque, low-rise (mostly ≤3 stories) cottages and small blocks with shingled gables, dormers, timber details; winding lanes, pocket greens, pergolas, and a strong street-tree structure. Interiors were compact but well-planned (indoor sanitation, efficient kitchens). Often cited as Germany’s most complete expression of the garden-city idea.

Community facilities & green: Embedded courtyards and greens, schools, shops, an artists’ colony presence, and woodland green belt (a green belt is a policy and land-use designation used to preserve open land around urban areas) intentionally retained around the settlement. Public realm was as curated as the houses.

Social idea: Krupp’s welfare capitalism scaled up—from early worker colonies to a mixed community for workers and salaried staff, using beauty + nature to promote health, loyalty, and social order

Peter Rowe views architectural design as a process of structured inquiry — a cycle of framing problems, forming hypotheses, testing ideas, and grounding them in social and environmental context. Port Sunlight (founded 1888 by William Lever) can be understood through this lens as a design experiment in merging industrial progress with social welfare and architectural beauty.

The Essen-Katernberg and Margarethenhöhe follow a similar line of thinking; Rowe would interpret Katernberg as a bottom-up adaptation of industrial urbanism—its design reflects economic necessity and social hierarchy. Margarethenhöhe, by contrast, represents a top-down social reform project, where spatial design embodies moral and aesthetic ideals about community and well-being. The former serves production; the latter aims at social uplift through design.

Problem Framing

Anthropometric Analogies: Port Sunlight’s homes were designed to meet the physical and moral well-being of workers. Houses included ample ventilation, sunlight, and indoor sanitation — far exceeding the cramped standards of urban workers’ housing of the time. Each family had private space and gardens, emphasizing dignity and comfort.

Environmental Relations: The village layout responded directly to its rural Wirral setting. Curving streets followed natural contours, and green belts separated housing from the factory zone. Parks and communal greens were integrated into the plan, promoting health and recreation — a deliberate contrast to polluted industrial cities.

Katernberg sits on relatively flat terrain, which facilitated rational grid planning and infrastructure expansion. Because of this, there was little morphological adaptation to natural features such as slope, vegetation, or water systems. Drainage and environmental management were treated mechanically—through engineered solutions rather than ecological sensitivity.

The settlement’s orientation and layout prioritize functional adjacency (proximity to the mine) rather than solar exposure, ventilation, or microclimate comfort. This contrasts sharply with the environmentally responsive curvilinear planning seen later in Margarethenhöhe.

Hypothesis Formation

Literal and Canonic Analogies: Lever and his architects borrowed from familiar English village forms — gabled roofs, half-timbering, and decorative chimneys — to evoke stability and identity. These elements were not copied but reinterpreted to express moral and aesthetic ideals within a modern industrial framework.

Typologies: Port Sunlight synthesized multiple building types — workers’ cottages, managerial houses, churches, schools, and art galleries — into a coherent whole. Each type served a social function yet contributed to a unified village identity. Both the Essen-Katernberg and Margarethenhöhe followed the same line of thinking.

Formal Languages: Over thirty architects were employed to create stylistic diversity while maintaining harmony through scale, materials, and rhythm. This variety reinforced Rowe’s idea of contextual coherence — design as a dialogue between unity and difference.

Testing and Iteration

Design was refined over time through successive housing phases (1888–1914). Early brick cottages gave way to more complex Arts and Crafts compositions, testing how architectural beauty could coexist with affordability. Each phase informed the next, turning the village into a living laboratory for industrial-era community design.

Both Essen-Katernberg and Margarethenhöhe are products of the industrial and social transformations of the Ruhr region in the early twentieth century. Each emerged in response to the intense pressures of industrialization, urban expansion, and the housing needs of a rapidly growing working class—but they embody two opposing conceptions of how architecture and urban form could structure society.

Contextualism and Precedent

Contextualism: Port Sunlight’s architecture was deeply rooted in its physical and cultural setting — a moral response to industrial Britain’s social ills. The plan engaged its landscape, sunlight, and green spaces to foster well-being and order.

Essen-Katernberg and Margarethenhöhe represent two contrasting models of early 20th-century German urban development within the Ruhr industrial region. Essen-Katernberg evolved as a working-class mining settlement, characterized by pragmatic housing near industrial sites.

In contrast, Margarethenhöhe was a planned garden suburb, commissioned by Margarethe Krupp in 1906 as a social welfare experiment promoting healthier living conditions.

Precedent: Lever drew lessons from earlier model villages like Saltaire and Bournville, adopting their social ideals but expanding them through stronger architectural expression. Traditional English vernacular forms provided precedent, yet these were modernized through Rowe’s “reinterpretation of type,” making Port Sunlight both familiar and progressive.

Conclusion

Applying Peter Rowe’s framework reveals Port Sunlight as a structured inquiry into industrial society’s housing problem. Lever’s designers reframed the issue of worker welfare as both a social and architectural challenge. Through precedent, contextual adaptation, and iterative design, the village became a model of contextualism — harmonizing environment, culture, and form to produce a humane industrial community.

The landscape used as a means to serve industrial efficiency rather than as a co-productive partner in settlement design. The settlement’s environmental response is reactive rather than generative, forming a pattern of ecological neglect typical of early industrial urbanism.

Swiss Air Headquarters

Location: 41 Pinelawn Road, Melville, New York

Architect: Richard Meier (recipient of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, 1984)

Completion: 1980s, during Meier’s peak “White Modernist” period

Architectural Style: International Style / Modernism

Key Characteristics:

-

Distinctive white façade featuring Meier’s trademark geometric grid system

-

Extensive use of glass to emphasize natural light and visual transparency

-

Open-plan interiors promoting flexibility, collaboration, and spatial continuity

-

Emphasis on clean lines, rectilinear forms, and carefully balanced proportions

Primary Function: Designed as the U.S. corporate headquarters for Swissair

Project Information

Objective: A new project is proposed to add to the existing site. Specifically, incubator housing for individuals entering the Swiss Air Corporation’s workforce. The demographic for this housing is those who cannot afford to rent locally. That number is 2% of total occupancy

Client: Swissair Headquarters

Total Occupants: 16 Occupants

14 Studio Apartment Units to be 500 S.F. ea.

2 Duplex Apartment Units to be 1,000 S.F. ea.

Circulation (Hallways) to account for roughly 1,200 S.F.

Lobby to account for roughly 300 S.F.

Community space approx. 500 S.F.

Total Area (Approx.) = 13,000 S.F.

Zoning Information

Zoning: Single-Purpose Office Building (C-2)

Height, Area, and Bulk Regulations

Maximum building height: 30’-0”

Minimum depth of front and rear yard: 75’-0”

Width of Yard on Street Side: 75’-0”

Width of Interior Side yard: 40’-0”

Minimum Lot Area: 3 Acres

Existing Building Site

Parking

Off-street parking required per § 198-47

Residential uses require on-site parking

No parking within:

20 ft (front)

15 ft (street side)

10 ft (interior)

20 ft (residential boundary)

Sun Path

Fall

Winter

Spring

Summer

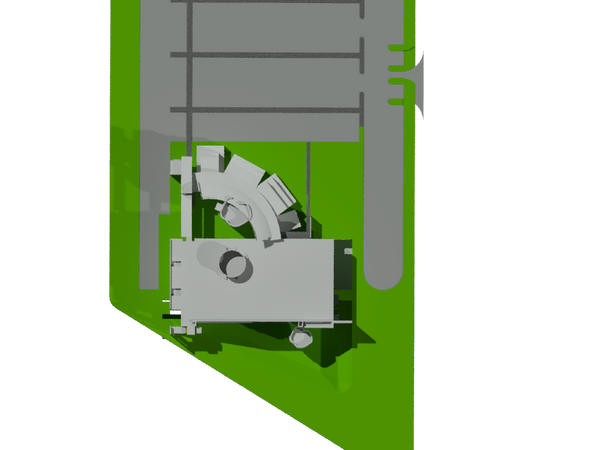

Existing Site

Basement Floor Plan

Second Floor Plan

First Floor Plan

Roof Plan

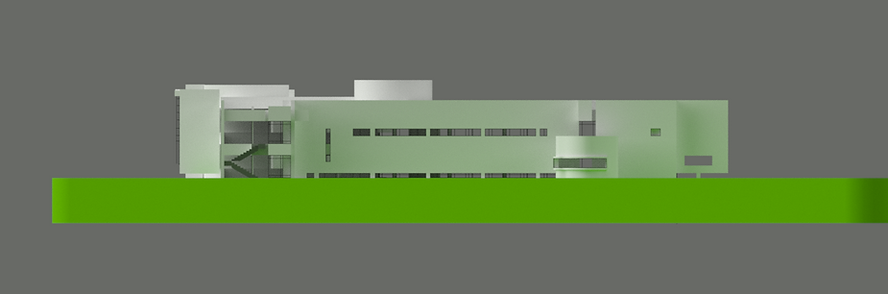

Existing Elevations

Front Elevation

Rear Elevation

Left Elevation

Right Elevation

Site Visit Pictures

Existing Building Diagrams

Preliminary Design 1

Design Concept & Heuristic: Drawing on Peter Rowe’s theoretical framework, the heuristic guiding Preliminary Design 1 is environmental. The design emphasizes environmental responsiveness through the orientation of the apartments. Each unit features a rear glass façade angled toward the north to optimize solar access, allowing natural sunlight to penetrate the living spaces. Additionally, the arched façade above the central hallway functions as a sunshade, mitigating direct sunlight within the circulation and common areas, which are designed as distinct, purpose-driven spaces. The building is 3 stories high with apartments attaching into each floor with their own back patio's. We have 14 studio apartments and 2 duplex's to meet all our employee's needs.

First Floor Plan

Second Floor Plan

Third Floor Plan

3D Axonometric Renderings

Roof View

3D Elevation Renderings

Front Elevation

Right Elevation

Left Elevation

Preliminary Design 2

Design Concept & Heuristic: For Preliminary Design 2, the guiding heuristic is metaphorical, inspired by the concept of a linear assembly line for workers. The design interprets this metaphor through a streamlined spatial organization, where the apartments are elevated above the parking area. Functionally, this arrangement allows the building mass to serve as a canopy—providing shade and protection for both the parking spaces and pedestrian walkways. Formally, the composition establishes a clear hierarchy of geometric volumes, employing a series of interrelated squares that reference Richard Meier’s disciplined use of geometry.

First Floor Plan

Second Floor Plan

3D Axonometric Renderings

Roof View

3D Elevation Renderings

Front Elevation

Left Elevation

Right Elevation

Preliminary Design 3

Design Concept & Heuristic:

For Design 3, the guiding heuristic is literal/formal languages, inspired by the Getty building by Richard Meier. We wanted to create another lookback at Meier's design as the focal point of this third design. It interprets this quite literally as an addition to the original Swiss Air building. The curved slope of the floors and roof can be used as both a terrace and/or a balcony, the use is determined by our client. There are two floors and a common area with access to both, as well as two staircases on each side for multiples fire routes. The circulation is open and the terrace/balcony faces at an angle from the South to avoid the harsh sunlight. We placed windows on the sides f the apartments facing outward similar to the ones on the Swiss Air building to create a similar resonance and connection with the additional apartment and the original building. We have 14 studio apartments and 2 duplex's to meet all our employee's needs.

First Floor Plan

Second Floor Plan

3D Axonometric Renderings

%20(2)-Temp0028.png)

%20(2)-Temp0035.png)

3D Elevation Renderings

Front Elevation

Back Elevation

Left Elevation

Right Elevation